I have always wanted to write a post titled “Reflections on China” but I had to go to China first, which actually happened a couple of months ago. I am a China enjoyer and everything I saw there just made this position stronger. Let me tell you the reason of the trip first then we go to my impressions.

1. The International Doctoral Forum at CUFE

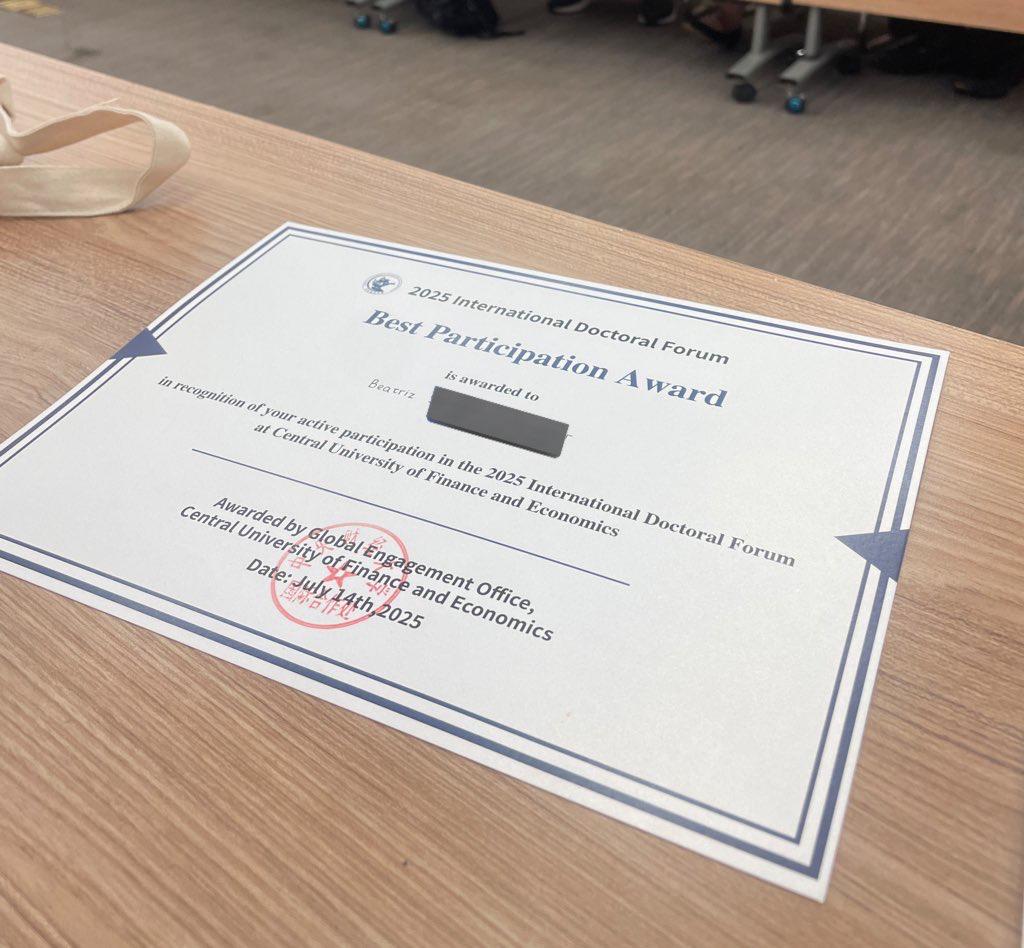

The Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing hosted its second International Doctoral Forum. The main goal of this 10-day meeting was to "deepen young scholars’ understanding of China’s economy and society while also broadening domestic students’ global perspectives". We (19 international students) were there alongside CUFE's most distinguished PhD students, and we all presented our research, which was super interesting because we are so used to seeing research on China being done by researchers abroad that we often forget there are thousands of great researchers in the country (they also have access to datasets we don’t! Too bad they don't have access to the rest of the internet, otherwise they would be unstoppable).

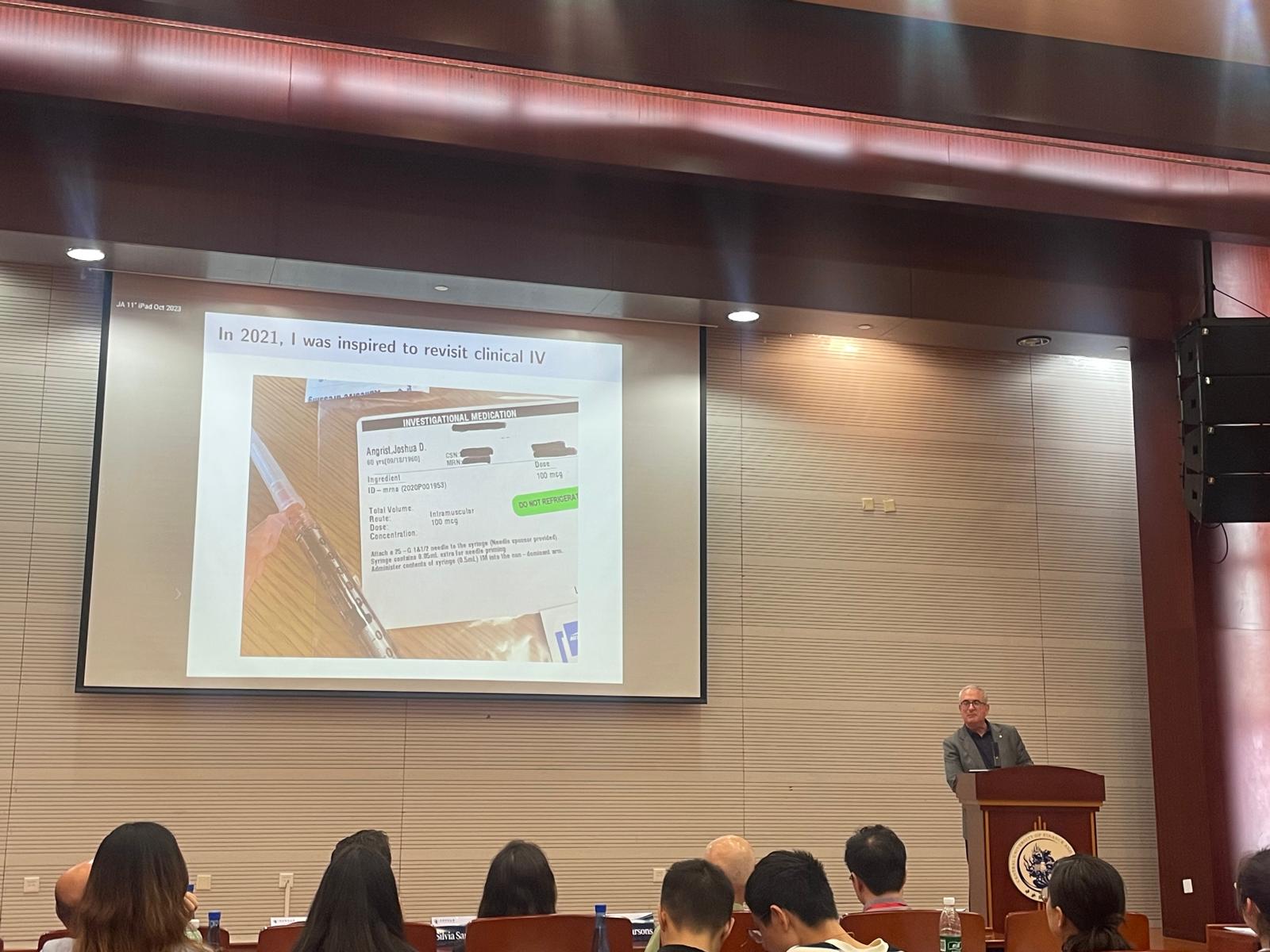

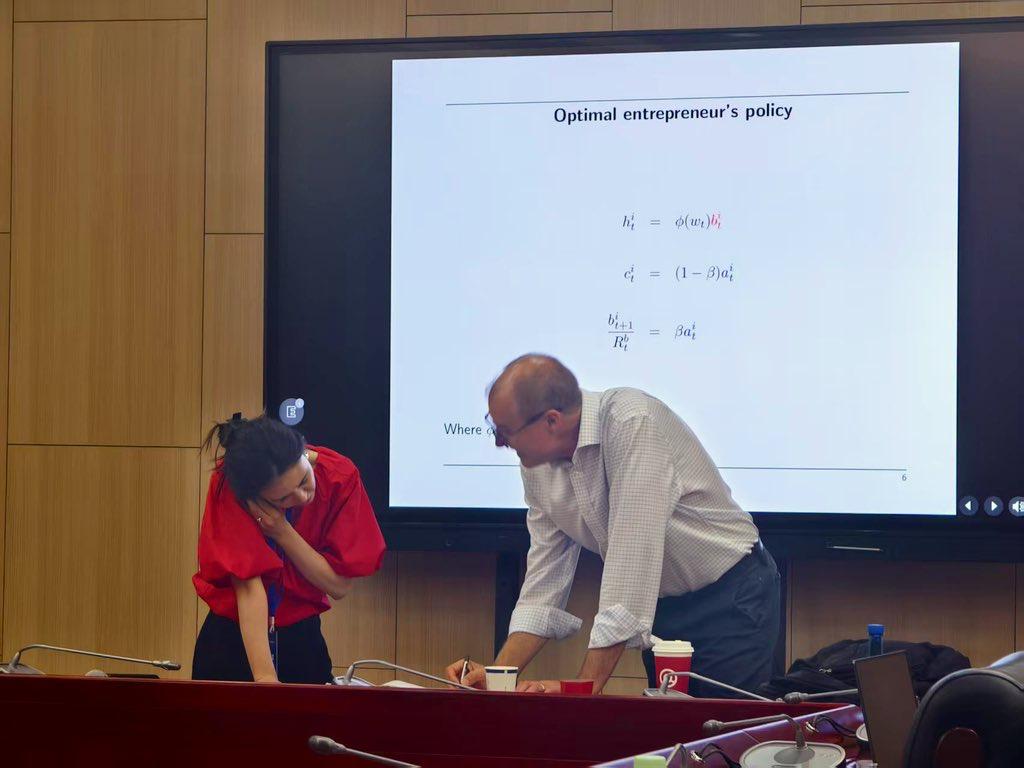

Not a single day was similar to the previous one, and that was a net positive. To open the forum, we had a lesson by prof Josh Angrist (he explained how IV should become the benchmark in research trials - I covered his paper previously in the newsletter). We had a course on macro-finance led by prof Vincenzo Quadrini, then the mornings would be dedicated to presentations by professors and students (I had the chance to present to professor Silvia Sarpietro, she was amazing).

We would eat lunch and dinner at CUFE’s canteen, and the menu changed everyday. Both periods were intense, so it was nice to have a short break in between with colleagues where we would talk about lots of things. These communal meals were the highlight for me. At night we would do miscellaneous cultural activities or just walk (actually Didi'ed) around the place.

On one of the days we went to visit the company Watchdata, where the CEO himself walked us through the history of the company (he also said we should learn Chinese so he could employ us). Another highlight of the forum was the visit to the mega city of Tianjin! We watched the Peking Opera at the Chinese Grand Theater and went to the museum. In some of the days where we had a couple of free hours, we went to the Summer Palace and visited the Great Wall on an evening tour. I recommend you do all of these if you have the chance :)

Professor Huancheng Du and Director Jianxin Ge (with the help of the most prolific volunteers I’ve ever seen) really put the greatest program in place and welcomed us with open arms. I had an amazing time and I would like to invite you (PhD student, Postdocs, event APs) to apply to next year’s edition when it opens for applications.

The official announcement is available here .

2. Getting to Beijing

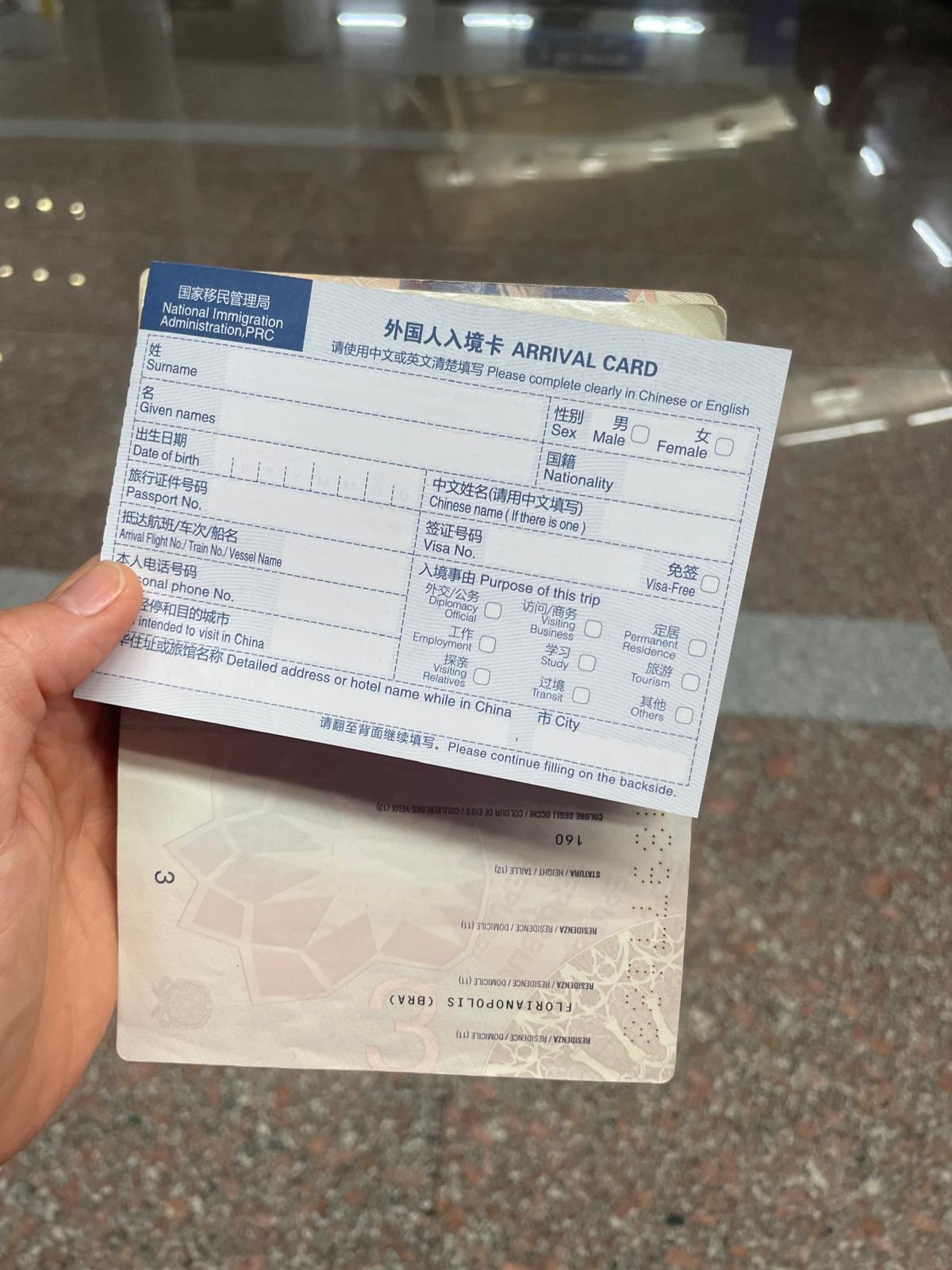

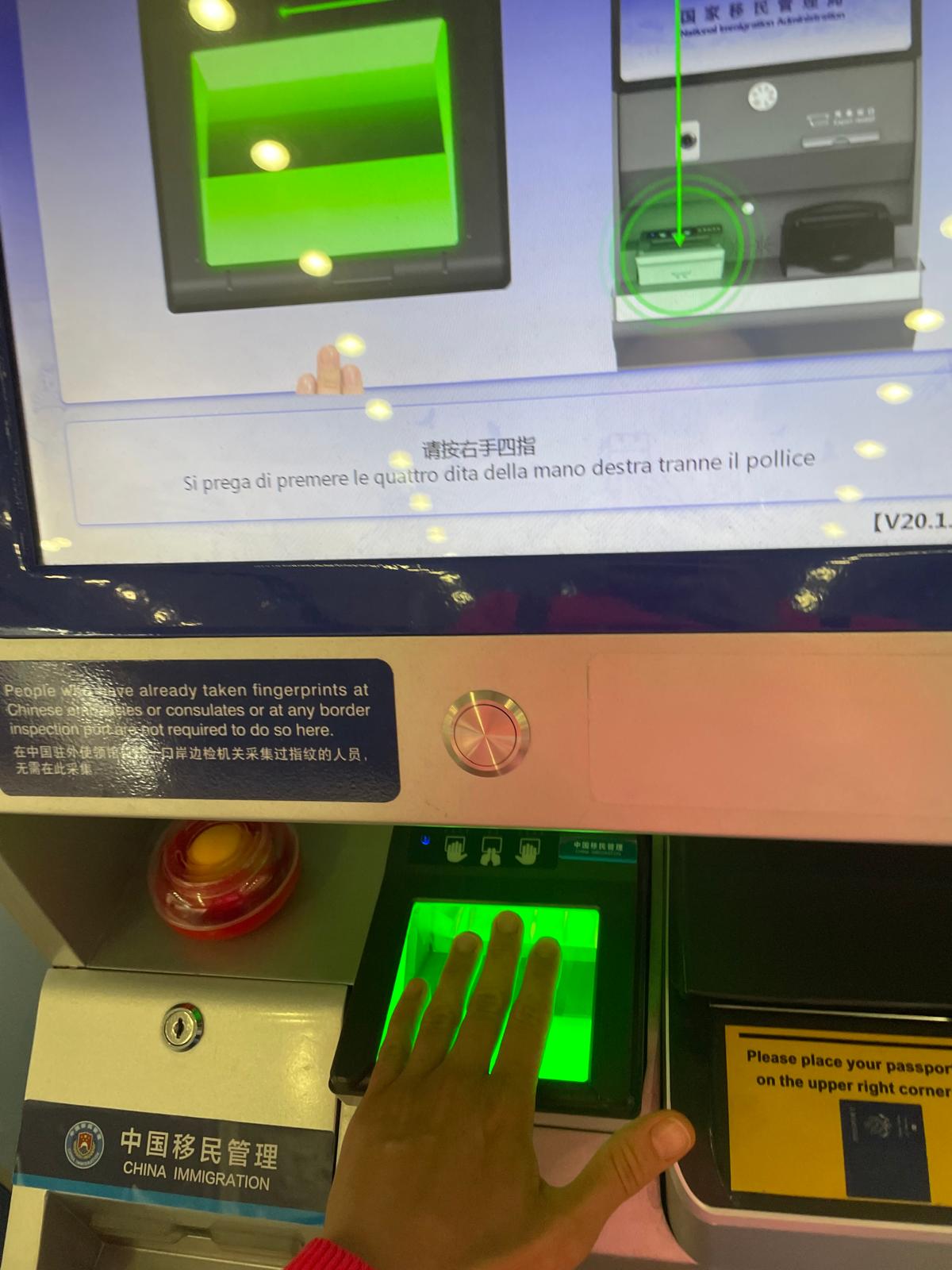

Now let’s talk about China. It is a vast country with millions of people, so it’s natural to expect for it to be a country of extremes. It is also expected to have very strict border control. When getting to Beijing airport, you immediately notice how layered and procedural the entry process is. Passports and visas are checked multiple times, photos and fingerprints are taken, and everything feels tightly managed. China has long held a tradition of using population and territorial management as tools of governance, and the border is the first line of that system. Strict control serves multiple functions: it protects political stability, it reduces the risks of terrorism and separatism in sensitive regions, it limits capital flight, and also maintains oversight of who enters and leaves the country. I’m sure the COVID-19 pandemic made these measures even more visible, but they existed long before. Unlike countries that treat borders as points of flow, China treats them as points of control. It was weird, but I felt safe.

After you have been through security (you will go through a similar process when exiting the country), it’s time to get to the city. You can either take the metro or a taxi. This is when the fun and chaotic part starts. Since I was there for the conference, we were given a guide on how to get around and which essential apps to download before arriving in Beijing.

None of your usual apps will work if you don’t have a VPN on your phone and computer, and not all VPN services work in China. You either register your bank cards in the apps before arriving, or do it there through a VPN. I didn’t want to risk it, so I spent a couple of days setting everything up. The apps I used were: Alipay (payments), WeChat (communications and payments), DiDi (ride-hailing, payment via Alipay/WeChat), Amap (navigation), and Meituan (food delivery and transport).

Regardless of where you are, you need to call a cab on the app because they don’t stop otherwise. It’s also extremely necessary to buy an eSIM card and install it before getting to China. I recommend Nomad, which I bought for one month and it worked perfectly. The eSIM is essential: when connecting to the hotel’s Wi-Fi, I needed a Chinese number. Without a friend’s help, I wouldn’t have been able to connect, since you can’t buy a Chinese SIM card there. For VPNs, I recommend LetsVPN. If you’re more tech-savvy, you can also try Clash Verge. Both worked well for me.

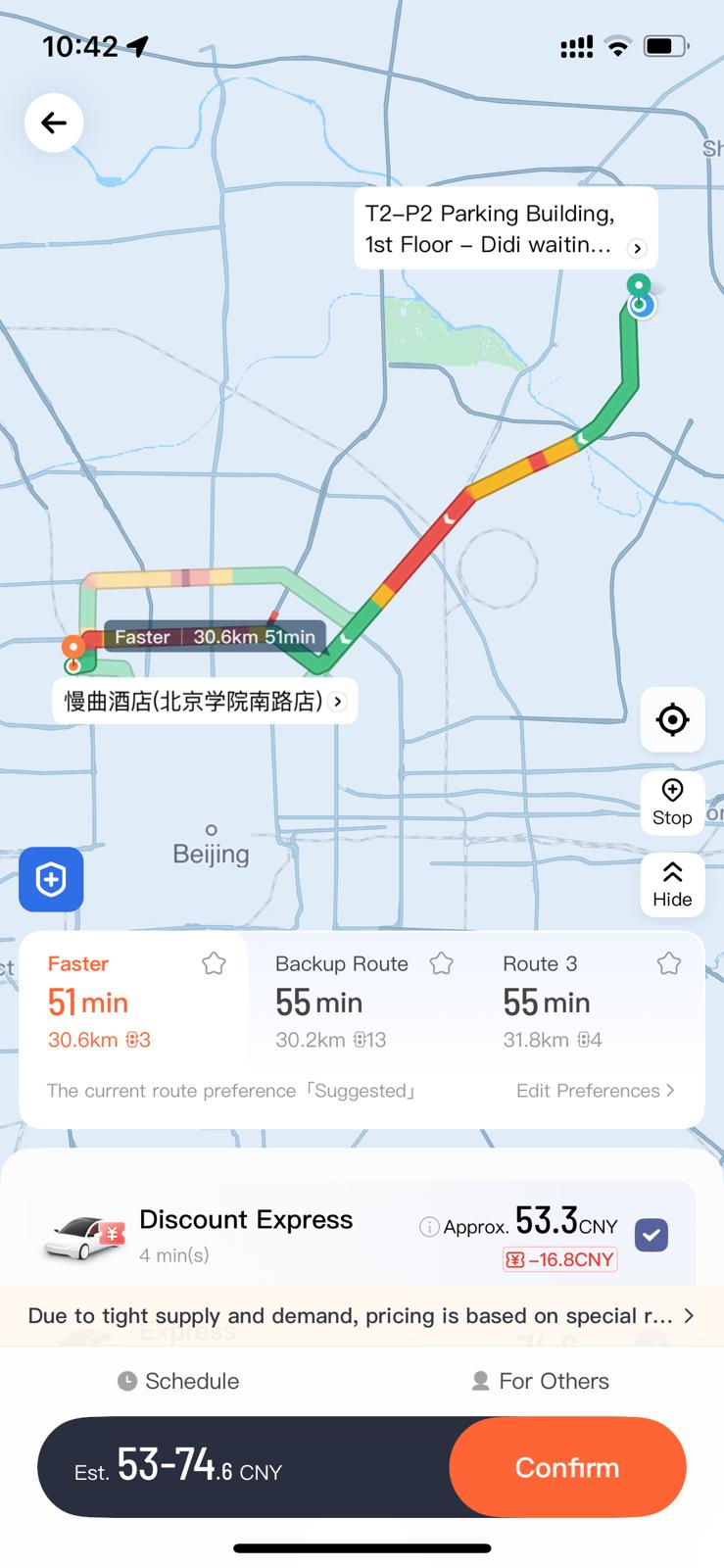

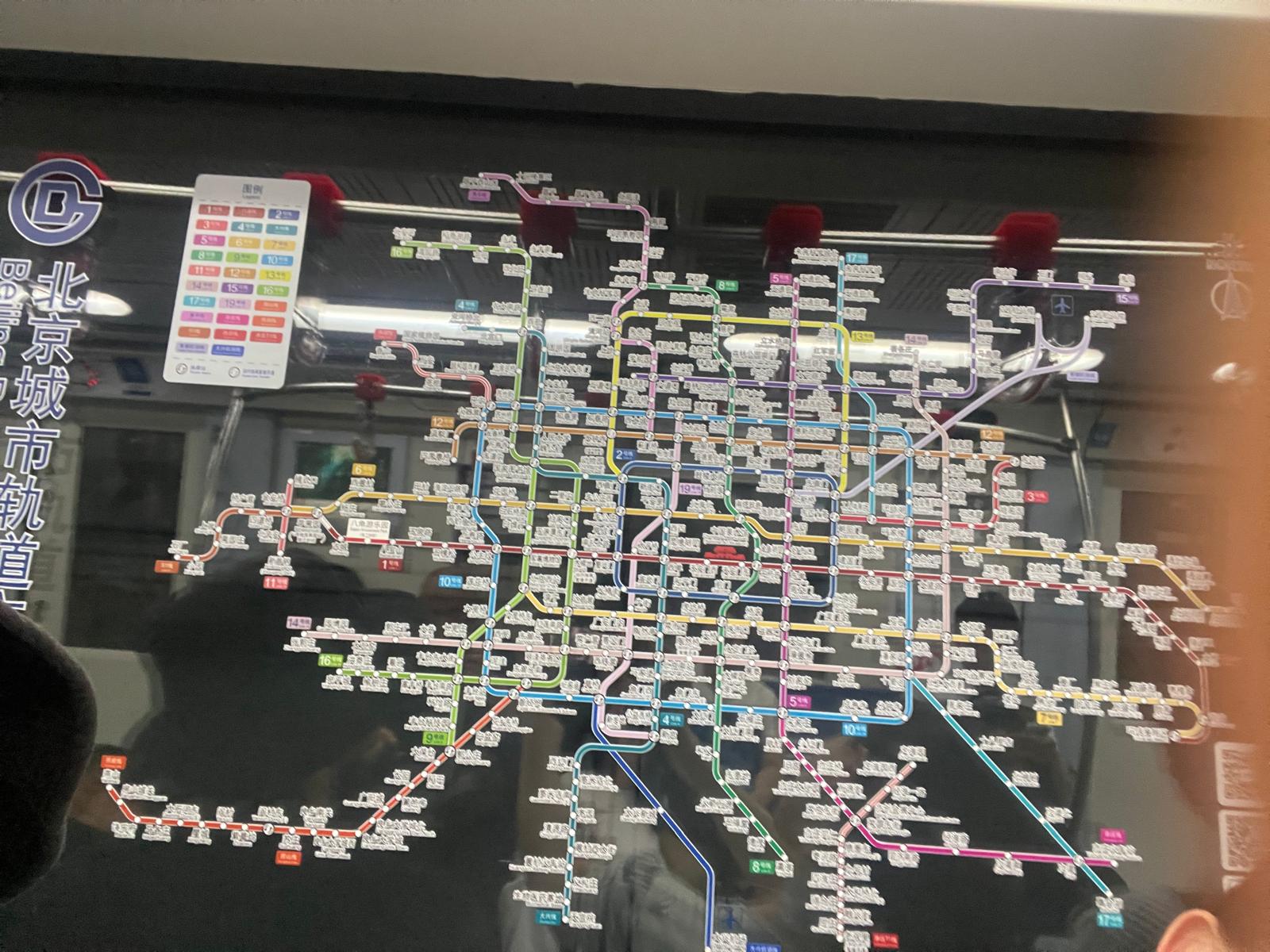

While at the airport, you can withdraw cash (though it’s rarely necessary since almost everyone pays through apps). I withdrew 1,000 yuan just to be safe and to give my dad some peace of mind. You can also grab a Starbucks before heading out. From there, you either take the metro, bus, or use DiDi (as I learned, DiDi doesn’t translate to “younger brother”, but it represents the honking sound). I chose DiDi because I had two heavy suitcases (I was staying for two weeks and needed slightly formal attire for the entire trip) and wasn’t completely sure how to get to Beijing. If you choose the metro, you can scan your physical bank card or tap the Apple Pay, or download a travel card directly to your wallet - the Beijing T-Union Transit Card, similar to DC’s SmartTrip or SF’s Clipper. We ended up taking the metro and the bus one day, and it was the cleanest, cheapest, and most well-organized metro system I’ve ever seen. I was in awe. The bus riding wasn’t bad at all. If I am not mistaken, you can register for a travel card with your passport through Alipay. I remember doing that (again, just in case), but can’t recall the exact details.

I have to confess: Beijing is cha-o-tic. It took me 15–20 minutes to find my driver (at the designated ridesharing area outside the airport) because we couldn’t communicate properly, even with DiDi’s in-app translation. You can’t count on someone to help you (though someone did in my case) because most people don’t speak English. I’m used to this; Brazil is the same. Taxi drivers will likely not even look at you, let alone engage in small talk. Some will ask for the last four digits of your phone number to confirm they’re picking up the right person, so at minimum you should know the numbers 1 to 10 in Chinese. If all else fails, show them your phone with DiDi open. From the airport to the city it’s a good 40 minutes to one hour drive because it’s far and also because of the heavy traffic. You should account for this on the way back. Also Beijing has 2 civilian airports (PEK, PKX) and a military one in Haidian District (but I doubt you will ever fly to this one). Please make sure you’re heading to the correct one because they are very far from each other. I didn’t see any smoke or air pollution, though, throughout the entire time I was there. It was warm, super humid, but the air was clean.

3. The City of Beijing

I am gonna sound stupid saying this, but Beijing is huge. I don’t think I could ever see everything the city has to offer, no matter how many times I return. And the Beijing of today is not the Beijing of yesterday: no man ever visits the same Beijing twice, for it’s not the same Beijing and he’s not the same man (Su Wang, if you’re reading this, I hope you know I was thinking of you when writing this poetic line). You should take advantage of all the forms of transport the city has to offer (especially the bikes!), but particularly you should use your legs and feet. I walked so much (in that heat nonetheless), and it allowed me to connect to the people (even though we didn’t speak the same language) and their lives in a more meaningful way. You will be able to catch the smallest details: in a building’s design, in someone’s clothes, on walls and pavements. You experience the old and the new standing side by side.

Beijing is also home to some of the best universities in China, most of them located within a 5 km radius around Zhongguancun (Peking University, Tsinghua University, etc.), and the locals are proud of them. There are also many parks, and they are unlike the parks I am used to. History and leisure are fused. At the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan), once the Qing emperors’ grand retreat and destroyed in 1860 by British and French troops, we (Olivia, Kira and I) walked past stone ruins that symbolise both imperial splendour and foreign invasion. When we visited, the park was full of life: families picnicking, students rowing boats, retirees practicing tai chi. We barely saw any other foreigners; most visitors were Chinese, a reminder that Beijing is first and foremost a pilgrimage site for domestic tourists (China is the world’s largest domestic tourism market). Yet these parks feel less like tourist attractions and more like living museums, where daily life unfolds among reminders of China’s past.

On the only afternoon we had free (Takshil and I), we ventured to Tiananmen Square before hopping on a bus to the Great Wall. I felt a bit conflicted standing beneath Chairman Mao’s portrait at the entrance, since Tiananmen carries such a heavy past. It has been the site of major historical events, including the founding ceremony of the People’s Republic in 1949, military parades, and large-scale gatherings. In 1989, it was the centre of student-led demonstrations that ended in a violent crackdown. Also there (after many, many passport checks) we saw several visitors having professional photos taken while dressed in traditional outfits. Women, men, and children rented old-style clothes (often hanfu or Qing-inspired) and posed against the backdrop of the Square walls. I reached the conclusion that it’s part cultural revival, part keepsake, and part social-media trend. It was actually the perfect background for people to connect with their heritage and take home a very personal memory. I wish we had more time to explore the Forbidden City, but unfortunately our hours were counted.

4. Venturing outside Beijing

From Tiannamen we took the metro to where the tour bus (which we booked the day before) would take us to Mutianyu, which is about 70 km northeast of Beijing. The Great Wall is not a single site, you can easily visit many parts, each with its own feel. Badaling is the most famous and most crowded, easy to reach and fully restored. Juyongguan is closer to the city and was once a key military pass. Jinshanling and Simatai stretch across mountain ridges and are popular with hikers, while Jiankou is wild and unrestored, dramatic but challenging. I don’t regret our choice to go there on an evening tour because we could experience the wall during sunset and at night. A band was playing the whole time, which gave the place a festive atmosphere. It felt less like visiting a monument and more like joining a celebration on top of the Wall. Highly recommend a tour.

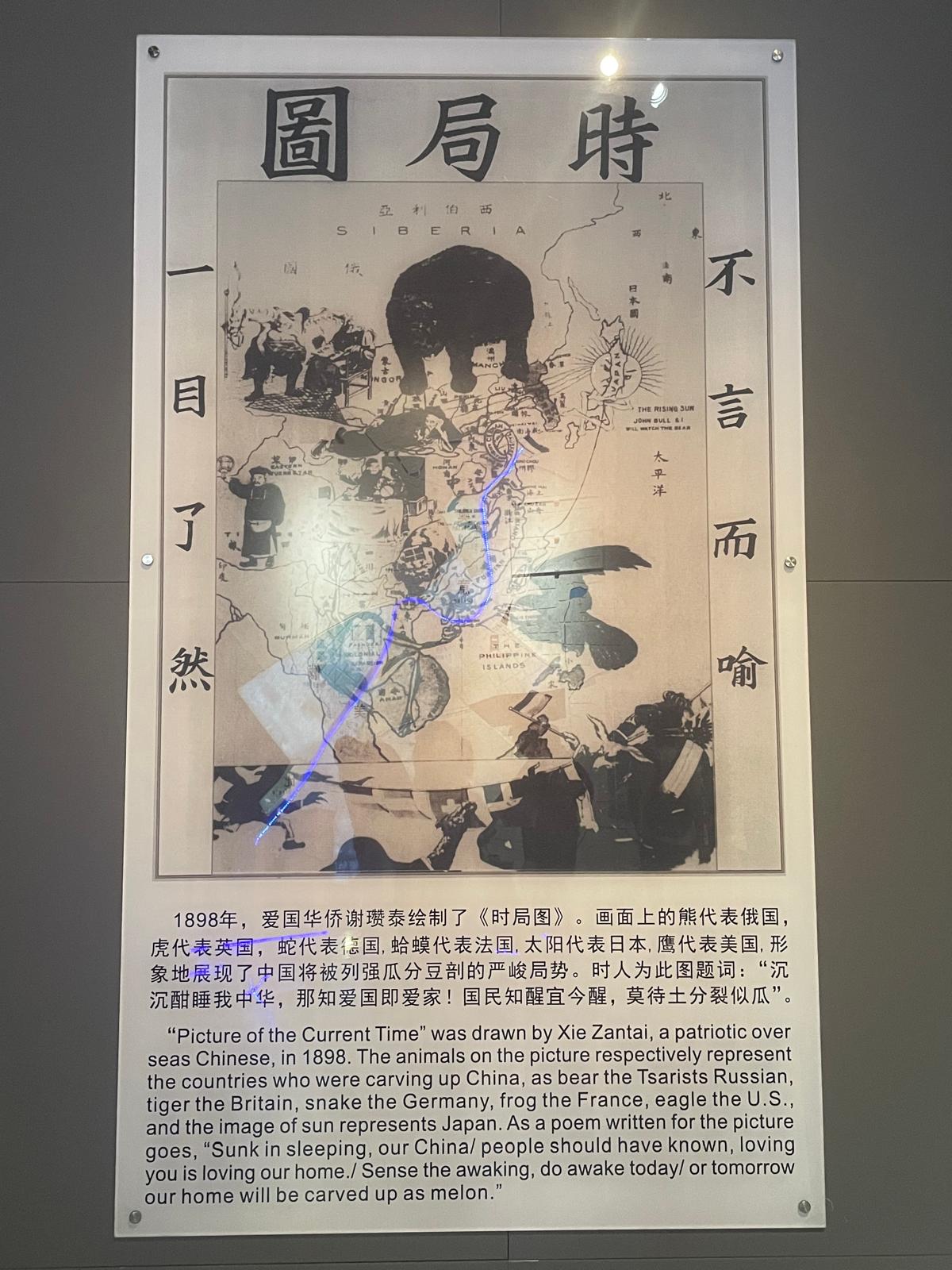

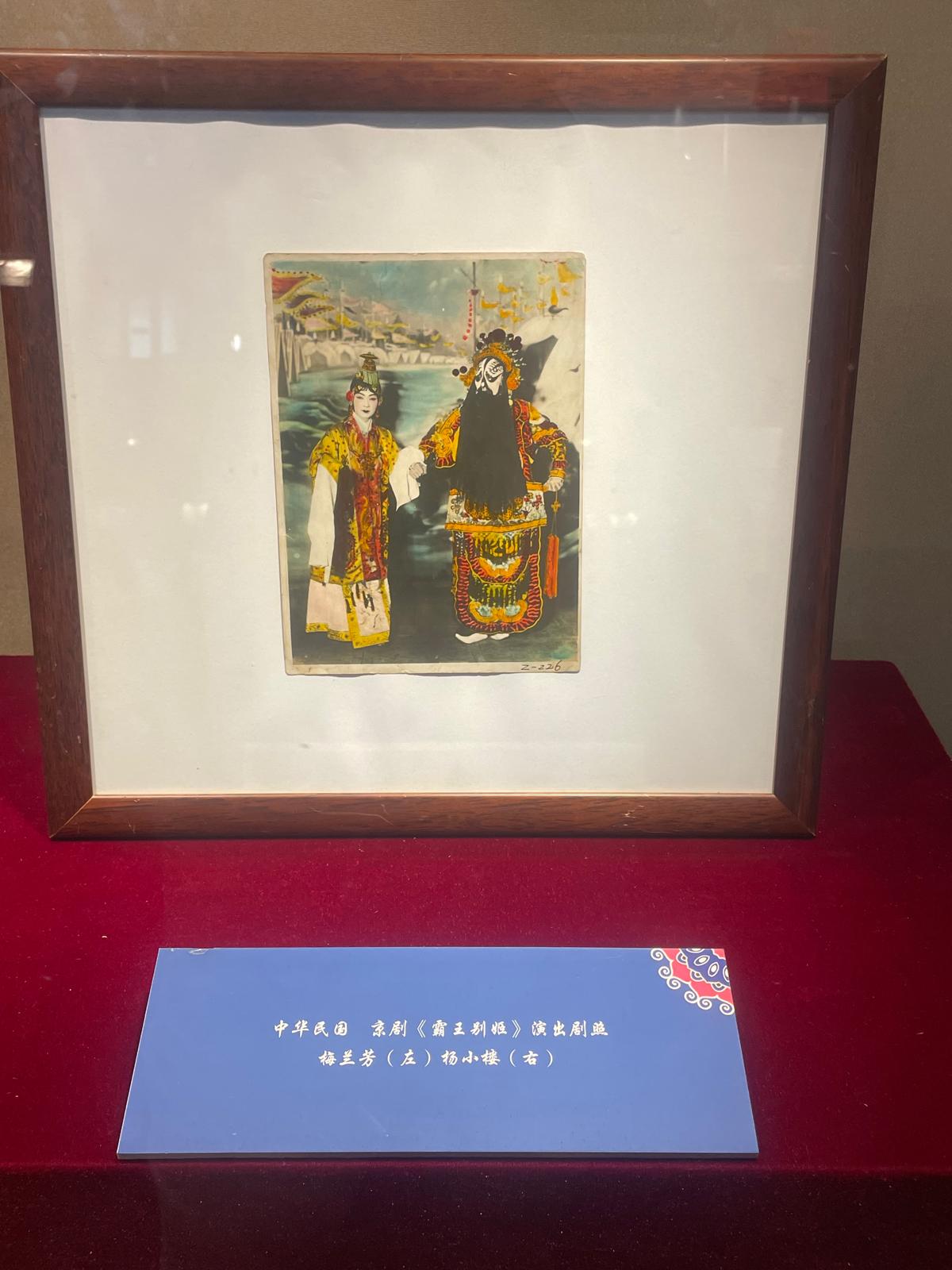

Our only other trip was to the city of Tianjin. We took the Sunday off to do that, by hopping on a high-speed train. For context, Tianjin is a major port city about 120 km southeast of Beijing. The high-speed train covers the distance in 30 to 40 minutes, which is extremely convenient (by car it would take you around two hours). Everything in China is built around getting you (or something, like food) from A to B in the shortest time possible. And Tianjin felt… European and American? I can’t fully explain why, maybe it was the buildings. The city was once divided into foreign concessions, each controlled by a different country (Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Belgium) all had their own zones, with one country holding control of a specific part of the city (something I learned at the museum we visited). The reason of our visit was to watch a Peking Opera performance. It has been performed for over 200 years, originating in the late 18th century during the Qing dynasty. It was a blend of singing, martial arts, very elaborate costumes, and painted faces to tell stories from history, folklore, and classical literature. Not that we understood much because our guide was too busy laughing at the jokes to offer us any meaningful translation. Once performed for the imperial court, it spread beyond and became a popular art form across China. Today it is recognised as part of the country’s intangible cultural heritage. It was lovely, and we had a great time, as did the rest of the audience, all Chinese.

5. Why I would live in China, and why you should travel there

Some of you reading might not know where I come from, and knowing this information will allow for a deeper understanding with regards to what matters to me in life. I was born and raised in a rural town in southern Brazil, by my maternal grandmother, while my mom and dad were busy running their businesses. We were poor and we all lived with her, up until my early teenage years, when my dad managed to buy a house. An infancy not too different from a kid in China in the 90s, as some of my close Chinese friends who grew up in that decade would relate having had similar childhoods. The difference is that they now have megacities near their birthplaces, whereas we in Brazil don’t. Our countries’ paths couldn’t have been more different. They tried and achieved, we didn’t even try and for that reason have failed. I nurture a deep respect for the people who built that country, for those now alive and for those who have perished doing so.

China feels surreal to me. Walking through Beijing and Tianjin, I couldn’t help but compare my own background with what I was seeing: a place built on centuries of history, reshaped in just a few decades into megacities that feel like the future. As an economist, I can’t help but think of this in terms of institutions and human capital. Which comes first? Some argue that strong institutions are the foundation, and that without credible rules, property rights, and state capacity, no amount of investment will deliver sustained growth. Others argue the opposite, that human capital, driven by a capable and educated elite, is what allows good institutions to emerge. China’s trajectory doesn’t fit squarely into either camp, but it suggests a sequencing: a technocratic elite consolidated power, built state capacity, and created institutions that could mobilise resources at scale. They poured money into infrastructure and education, then gradually opened space for markets once industrialisation had taken root.

Brazil, by contrast, began from a comparable starting point in the mid-20th century. We also had industrialisation, urbanisation, and an educated class. But we never built institutions with the same consistency or authority. Our political system remained fragmented, our state weak, our investments in education ineffective. Macroeconomic instability ate away at progress. Where China channelled resources strategically into long-term development, Brazil found itself between short-term fixes and chronic inefficiencies.

I felt this divergence, it is personal. I recognise parts of my own childhood in the stories of my Chinese friends who grew up in the 1990s, yet today their country has propelled itself forward while mine has stalled. It goes beyond just culture (they are somewhat similar) and work ethics (they are opposites), it is institutional. China tried, and it achieved. Brazil never even tried. And this shows in economic outcomes and in daily life. In China I felt safe, even in crowded streets, late at night, something I cannot say about Brazil. Order, infrastructure, and state presence create a sense of security that is hard to measure with numbers but impossible to ignore when you experience it. It is why, if given the choice, I would live in China, but I could never return to Brazil. You might say “but they have an authoritarian state, that allows for no dissent; they have CCTVs everywhere, and if you dare to criticise the government, you go straight to jail; their most successful entrepreneur was nowhere to be seen for months”. Well, yes, and no. For my China hawks, I don’t want to downplay the political realities, but I also can’t ignore how much order and predictability this model produces in practice. It is easy, as an outsider, to focus only on restrictions, but when you live (even briefly) inside the system, you see what it delivers: working transport, safe streets, functioning infrastructure. In the UK you can be arrested for a tweet, in the USA people fall victim to violent crime on public transport (sometimes even after the offender has been arrested many times before), in Brazil the Supreme Court has run ‘fake news’ inquiries that ordered arrests and account blocks. Tell me, where should I move, if what I want is social cohesion and a functioning rule of law? I am a libertarian, but I am also realistic, and I understand that a fully libertarian society is unattainable as of today. Words are not violence, but physical violence is violence. Every country makes trade-offs between freedom, order, and security, but the question here is which set of compromises you are willing to live with? The Chinese government works for itself and for the Chinese people. Who does your government work for?

So even if you disagree with what I wrote, I still think it is worth going there and seeing for yourself. See its flaws, see its strengths, enjoy the food, learn its history, get to know its people. The only way we can grow as humans and work towards better living conditions is through a mutual understanding of ourselves and our different realities. I plan to go back, maybe rent a car and drive through the countryside, visit Chongqing, Xi’an, and the southern provinces. I want to see my friends again (I miss you all), and I want to see how Beijing has changed since I left. China is too vast and too complex to be captured in a single trip or a single post. All I know is that I want to return, to learn more, and to keep expanding these reflections.